I’ve been procrastinating on this post. It started out as an idea from my publisher (Manning) back in April, just as my book was getting closer to being wrapped up, to make a decent argument about why it’s a great time for the web developers of the world to start using Web Components.

I thought a post like this was a fantastic idea, so I immediately agreed. After all, a lot has happened in late 2018 and early 2019 to finally prove Web Components are ready to go.

The reason for my procrastination was simple. At that time I’d started seeing some great beginner-oriented posts around Web Components that captured some of my same points and excitement. And, of course, as things always go on the internet, there were some Web Components killjoys that came out of the woodwork to stomp all over the excitement.

It’s OK — no technology is for everyone or every use case. But as the internet goes, if someone prefers their technology over yours, they’ll definitely make sure you hear about it! I can’t think of a successful framework/technology/platform yet that hasn’t gone through this at least once.

So, that’s where the Web Components discussion was in late spring and early summer of 2019. It’s why instead of this post, I decided to write a more technical one on the new Constructable Stylesheets feature in Chrome and how you can easily use a design system in your Web Components with it.

Anyway, I think people are finally a bit bored with arguing, and my book is now published (37% off with code: fccfarrell)! So, I think it’s a great time to revisit Web Components. Are they finally ready?

Technical Readiness

I think the easiest measure of whether Web Components are ready is whether they actually work. Can I drop one onto a page as a custom element and not have to worry about compatibility in modern browsers? Finally we’re in a situation where things are looking really great.

In the past, the big holdup has always been browser adoption. We’ve spent far too long on the edge of our seats waiting for all major modern browsers to support Web Components, hoping the standard didn’t just fall apart as they sometimes do when browsers don’t actually end up supporting the feature you want. Prior to fall 2018, only Chrome and Safari were good to go.

It all started to change in October, however. Firefox finally delivered Custom Elements and the Shadow DOM. While Custom Elements have always been an easy drop-in polyfill, the Shadow DOM is way more complicated and harder to use without native support. These two web standards are at the core of what we mean when we talk about Web Components. They enable us to create truly encapsulated bits of UI that can be wrapped up in a single tag and dropped onto a page easily without fear of conflicting with elements and style on the rest of your page, as we web developers have been plagued with for ages.

While Firefox was great news, it wasn’t the end of the story. Microsoft Edge was still the holdout. We knew that Web Components were under consideration and possibly in development, but that’s as much as we knew until recently. Then in December, Edge announced that they would be switching to Chromium, and Web Components would be picked up as a result. April brought us a developer preview release of the new Edge, and in the summer of 2019 we saw the same developer preview on MacOS, followed by the Edge Beta being released as recently as late August.

So, now, we have Web Components support on all major modern browsers. As someone who’s been working with Web Components since around 2013, I couldn’t be more thrilled to see this vision come so far. Even better, we’re seeing some major usage. In February, Google’s Polymer team joined a conference call with other framework developers for a sort of “state of the union.” They reported that the Chrome team was seeing that 10% of all page visits in Chrome included Web Components usage. Of course, YouTube likely plays a big part of this, as well as other Google owned sites. Even so, we’re starting to see Web Components extend to other major sites like Github, and just now to Apple Music.

Redefining Success

Mission accomplished, right? In some ways, absolutely. The technical bits are there and people are using them successfully. It’s now time to redefine success and acknowledge that there are other aspects to this experiment that started several years ago.

When we talk about any new workflow or technology, even beyond web development, I would argue that there are three major aspects to discuss:

- Does the technology work?

- How is the developer experience?

- Is the community welcoming and supportive?

There are so many nuances to each aspect, but optimistically, I think we can cross #1 off the list. Nothing works 100% for all use cases as “Custom Elements Everywhere” aims to demystify, but generally speaking, Web Components do work! Those naysayers that I mentioned above? They’ll argue over #2: the developer experience.

Developer Experience

The developer experience is so subjective that it’s impossible to gauge how good it is. It’s not just that developers have opinions on their favorite ways to code; it’s also what they build that varies so much. Because of this, talking about the right way to author on the web can get as heated as any political or religious debate. This is exactly where we were a few months ago: in a “back and forth loop” which had me procrastinating on this post.

Like I said, this lively battle is par for the course with anything. Any framework like React or Angular or Vue, no matter how good, has its haters. Zoom out a level and you’ll see the same discussions about the web in general. Or even Mac vs Linux vs Windows. To be honest, when people cared enough to begin passionately discussing their pros and cons this spring, it felt a bit like a rite of passage that took Web Components to the next level.

OK, so people are talking…and arguing. Does that mean Web Components are automatically amazing? Of course not! It does however surface some of the amazing efforts by the Web Components community, as well as some of the unmet needs that web developers have faced that Web Components might solve.

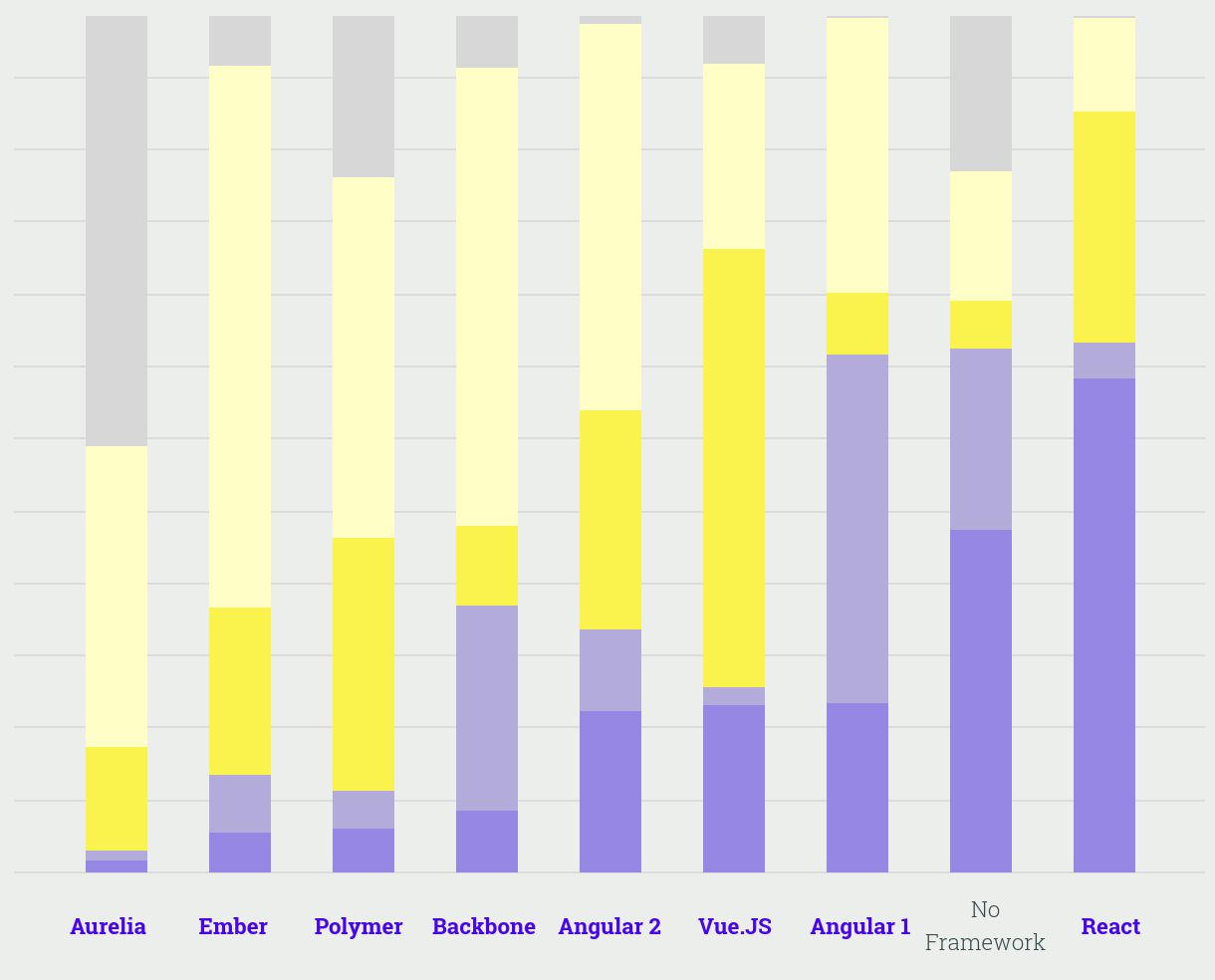

My philosophy when writing Web Components in Action revolved around a big unmet need that I saw Web Components solving. There is a contingent of developers out there who love making stuff on the web but don’t want all the complicated tooling or a framework getting in their way. When I saw the “State of JS” results from 2017, I realized I definitely wasn’t alone. Even more recently, this post on “Going Buildless”caught my eye.

Web Components solve a huge need by making UI components a foundational part of the web. UI components have been around forever on other platforms. Components, at a minimum, provide your project with structure and organization. In my opinion, they started getting good on the web with Angular and React. But with those frameworks/libraries you get a lot of baggage. Baggage can be great if you use it, but if components are really the only thing you want, why bother with all of that other stuff in popular libraries when you get it free from the web platform? There was a tweet from a while ago that really stuck with me:

This was at a time when lots of folks were excited about Web Components and they made the bold claim that they would replace your favorite frontend framework. As you can imagine, there was lots of pushback on these claims.

The tweet does a good job of setting expectations for those who are skeptical. It makes clear that Web Components, while providing a great foundation, do not provide features beyond making components first class citizens on the web. I’m thinking of things like routing, binding, and state management.

Here’s the thing, though: you don’t always need those features. I’d also add that in many cases, it can be pretty easy to write those features yourself, or pull in any number of tiny libraries that do that one thing well.

That’s not to say that my philosophy is for everyone. Some of the recent debates are around simplicity and elegance in writing your code. Vanilla Web Components get you really far versus a normal vanilla JS project where things tend to devolve into code spaghetti. Code organization is so much better when you can group into components and nest them without worrying about style leakage. When you dive into the code for each component, however, things can get a bit verbose for more complex UI and you’re still left to your own devices for code organization even if it is on a smaller and much more manageable scale. Enter the “religious” wars where we’re fighting over the most concise and elegant way to write UI code!

Web Components are starting to answer these calls in a big way, though. The obvious place to start is with the Polymer Project. The team is now focused on delivering LitElement and lit-html. To be honest, I was pretty happy with vanilla Web Components for so long that I didn’t give those tools a proper go until recently. I wrote a bit about them, mostly lit-html, in my book and discussed some things it was really good at, but until you’ve tried your hand at declarative programming, you tend to miss their true power.

Declarative programming is really just a design pattern. It’s what React is known for, and now we’re seeing Flutter and SwiftUI adopting the same style. You’re essentially creating a data model and rendering a view based on that. With every change to the data model, you re-render, never touching the actual elements in the DOM. In the past, I’ve done things imperatively. The user clicks a button, then you manipulate the actual DOM element or elements to reflect what the user intention was. It can get messy, but with experience, it doesn’t have to be.

I can totally see why some folks coming from React are so adamant about adhering to this pattern—it’s really nice! But it’s really only feasible when the DOM can be diffed. Meaning: if one thing in the DOM changes, it’s going to hurt to re-render everything in the component or the page. You only want to alter the aspect of the DOM that changed from a render.

For a while, React was the only major JS library to enable this. Enter lit-html. I’d argue that it’s barely a library. I’d call it more of a tiny imported utility that does exactly what I described React was doing. In lit-html’s case, however, the overhead from React is gone. Virtual DOMs are not created and diffed. The diffing is done on the real DOM. We’re left with an extremely lightweight, very targeted, and incredibly performant solution. As an ES6 module, it’s used easily with absolutely no frontend tooling or any extra help. Even React’s JSX is gone in favor of template literals and template tags native to JavaScript.

LitElement furthers lit-html’s declarative paradigm by creating a base class that extends your component to do some extra things that are normally verbose like keeping your properties and attributes in sync. With all the momentum behind LitElement right now, we’re seeing some great solutions on top of it. Those tiny solutions I mentioned before for vanilla components have a growing LitElement story as well. Do you fancy state machines? Try lit-robot. Want a great MobX solution for LitElement? Try lit-mobx from my great Web Component minded colleagues at Adobe.

Does this mean that this is where Web Components are going? Not necessarily, it’s one of the places Web Components are going. The Polymer Team is doing some amazing stuff, but Web Components aren’t one-size-fits-all. It’s a standard to build on top of, and lots of folks are doing just that.

Like hooks? Perhaps checkout the newer Haunted library, or it’s LitElement variation, which adopts the hooks design pattern popularized recently by React.

There are a number of great projects that have sprung up using Web Components as their basis. Salesforce, for example, has an amazingly comprehensive component library and ecosystem. To be honest, I’m not knowledgeable at all on their wider development platform, but judging by their Lightning Web Components developer’s guide, they have something to be proud of.

Ionic is another company embracing Web Components. Their Stencil toolchain actually compiles to Web Components. As a nod to the standard, and a bit of a shot at frameworks that tend to drift from it, they advertise that “Stencil doesn’t fight the web platform. It embraces it.” Ionic is fairly well known for their mobile tooling. With Ionic v4, they’ve switched over to Web Components with a nice library of components to go with it. Ionic Native should prove to be a great way to build Progressive Web Apps, mobile, Electron, and web from the exact same Web Components.

Speaking of compiling to Web Components, a number of projects with a much smaller ecosystem than Ionic aim to compile standalone Web Components themselves. This includes projects created to compile React, Vue, and/or Angular components to Web Components. Another project worth mentioning lately is Svelte. Though the author, Rich Harris, has been very vocal about why he doesn’t like Web Components, Svelte offers a way to compile to them regardless.

Vaadin Web Components were a very early entry into this space. While Ionic and Salesforce were building more of a platform/ecosystem, Vaadin (https://vaadin.com/components) stuck to providing a great set of components. I actually think it’s pretty interesting that one of their target audiences is Java developers. Java folks have plenty of concerns and choices of their own just like the frontend world, but I imagine that giving them UI components that just work takes a significant cognitive load off so they can focus on their Java ecosystem of choice. Even ignoring most of their UI components, the non-visual vaadin-router seems to be the component of choice for many Web Components developers who just need a router for their application.

I know I’m flat-out missing many entries into the Web Components space. In fact, most of the entries I’ve just mentioned, I haven’t even tried. It’s a lot to keep up with! It’s certainly not clear if there’s a horse to pick in this race. In fact, after I published this post, the author of webcomponents.dev chimed in hoping to be part of this round up! True overlook on my part, because its crossed my Twitter feed a few times. While I am currently set in my developer ways with my favorite IDE (hence not checking it out in depth), I can’t argue the usefulness behind a Web Component ecosystem as they provide, complete with code editor and integration with a huge number of UI libraries. This also reminds me that I forgot to include Storybook as a way to build components in isolation, see how they interact together, and document them.

Bottom line is that most of what I mentioned seems to be a “right tool for the job” situation. Underlying them all, though, is this new set of standards. It’s why in my book I decided to ignore most of the frameworks and libraries and simply focus on you, the browser, and plain HTML/JS/CSS. Grasping the basic concepts behind Web Components will give a great foundation for how any of these libraries work.

Do all of these great projects mean that you’ll never use plain HTML/JS/CSS in practice? Nope! I’ve hung on to writing Web Components this way for a while and it works well. As I’ve said, though, lately I’m really enjoying using lit-html for more complex UI, and perhaps I’ll dip my toes into LitElement soon as well. However, I’ve also seen and worked on some components that aren’t complex because of their UI but are complex because of other reasons.

One such component is the Shader Doodle component that I lightly contributed to. The goal of this project is to componentize amazing WebGL shaders that work on the popular Shader Toy website so they can run anywhere simply by dropping the <shader-doodle> element on a page. This is a great example of a Web Component that has no UI. There is simply a canvas and some script tags. Really, there’s no reason to bring in even something as lightweight as lit-html here. The only element used here is a <canvas>!

I’m also working on a few 3D and Mixed Reality-based components which I hope to share soon that also only use a <canvas>.

To me that’s the power behind Web Components. They are just a new set of standards that work for a huge number of use cases. And this is why in my book I chose to go as close to the browser and the standard as possible, empowering readers to get familiar with the foundations and continue on in any direction they choose.

Community

Now that I’ve covered the tech and developer experience, from an admittedly non-comprehensive view, community is the last point to get to. It’s also arguably the weakest link when we ask ourselves “Why Web Components Now?” But it also presents a pretty big opportunity for engagement with a smaller community that is growing every day.

Web Components in their current form and level of support are quite new. There is a wealth of articles dating back to 2011, but many are dangerously outdated. There were even a few books that sprung up in 2015, but these are unfortunately also outdated because the standards have been changing.

That said, in the past year, and increasingly in the past few months, I’ve seen quite a few blog posts on Web Components come my way. Obligatory “to do” app included! Additionally, the first modern Web Components book was released last November by Corey Rylan. I’ve bought the book myself to compare notes, and, quite frankly, I think that both his and my book approach things just differently enough that both are worth a read and you’ll get different and valuable takes.

As much as the community is really getting started, an argument can be made that now is the time to get involved. There’s lots of ground to cover! Web Components aren’t React or Vue or Angular. They are a standard that is reaching across many different use cases in many different ways, and as such, do need a lot of different voices chiming in. How can you add your voice? One way is to join the Polymer Slack channel. You might have mixed feelings about a corporate overlord like Google being the voice of Web Components. That’s perfectly fine, but the fact is that the Polymer team is really trying to help this community succeed however they can. Yes, you’ll hear more about LitElement and lit-html there, but the folks have been extremely nice and very willing to help each other.

For more neutral ground, though it’s still Google-owned, webcomponents.org is another great Web Components resource. Because it’s already getting a bit dated, the Polymer team has put out a public call for ideas on rebooting.

Despite the Polymer team doing a fantastic job, there probably should be a resource that’s not owned by a company. Open-WC is exactly that. There are a number of great open source projects created by Open-WC authors to help the Web Components ecosystem. One big leg up for Web Component development provided by Open-WC is their es-dev-server. I begrudgingly got on board with their server vs a typical dumb http server. Sometimes I try to be a browser purist to my own detriment. ES6 module importing doesn’t need to be complicated with long paths to your node_modules folder. Import maps should provide the ultimate solution, but until they get wide support in all browsers, es-dev-server is a pretty nice thing to fire up and get developing!

The big point to come back to, is that yes, the Web Components community isn’t as well formed as other dev communities that have been around for ages. We’re really just getting started, and there’s lots to do, and many voices to listen to. It’s an exciting time to get involved. If you’re in the Bay Area, you might want to check out the first Web Components meetup on September 23rd (unfortunately full up, but check the wait-list). Or, if not, keep your eyes on thisdot.co for more online meetups like this one.

Again though, if you’re brand-new to Web Components and just don’t know where to start or where they will lead you, you might want to check out my brand-new book: Web Components in Action.